Fack Ju Göhte is the title of one of the most successful German comedy films in recent times. A EUTM application by Constantin Film Produktion GmbH for the wordmark “FACK JU GÖHTE”, mostly for merchandising products, was rejected by EUIPO for being “contrary to public policy or to accepted principles of morality”. On appeal, the Board of Appeal confirmed the EUIPO decision, finding i) the proposed mark resembled the English expression “f**k you”, although spelled differently; ii) the relevant consumers – i.e. those of German speaking countries – would perceive the mark as vulgar and shocking; iii) the reference to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe could only increase the immorality of the mark; iv) the popularity of the film could not lead to a different conclusion.

On January 24, 2018, the General Court (GC) confirmed this decision (case T-69/17). It held that i) the misspelling of the words was not sufficient to give a satirical or playful connotation to the mark; ii) mark itself had to be assessed, regardless of its reference to a movie title; iii) the fact that the movie had been seen by millions of people could not lead to the conclusion that people would immediately associate the mark to the film, without being “shocked” by it.

While the outcome is perhaps not “shocking”, actually quite expected, the GC decision is noteworthy because it affirmed that “as EUIPO noted […], it is undisputed that in the field of art, culture and literature, there is a constant concern to preserve freedom of expression which does not exist in the field of trademarks.”2. Now, what may be “shocking” is that neither EUIPO nor the GC explained why “freedom of expression does not apply in the field of trademarks”. Should it? Well, we do not know about trademarks, but the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), less than a week after the GC’s ruling, pronounced an important decision on freedom of expression in the field of advertising (Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania, 30 January 2018, application no. 69317/14):

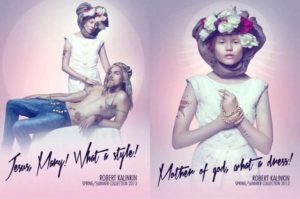

A Lithuanian fashion company (Sekmadienis Ltd) was fined, by the Lithuanian government, for publishing ads deemed to be contrary to public morals (see below the ads, depicting images of Jesus and Mary with phrases like “Jesus, what trousers!”, “Dear Mary, what a dress!”, etc.).

Alleging a violation of its freedom of expression – under article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights – Sekmadienis filed a complaint with the ECHR. The Court upheld this on the grounds that “freedom of expression also extends to ideas which offend, shock or disturb”. According to the ECHR, freedom of expression cannot only be applicable to “information” or “ideas” that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive because “such are the demands of pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness without which there is no democratic society”. Thus, freedom of expression can be invoked against limitations of free commercial speech as advertising, while it does not apply (according to the GC and EUIPO) to trademarks, among whose functions the commonest is that of advertising. In the 2011 judgment Interflora (C-323/09, §39), the CJEU said precisely this: “…a trade mark is often, in addition to an indication of the origin of the goods or services, an instrument of commercial strategy used, inter alia, for advertising purposes or to acquire a reputation in order to develop consumer loyalty. Should thus Constantin appeal to the ECHR and if it did, and won… could it get a registration?

While we’ll have to wait and see whether this discrepancy shall be resolved and if so how, it is interesting to look across the pond to the US, where similar issues have been discussed in recent years. In Matal v. Tam (582_US) of last June 2017, the US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) declared the Lanham Act’s ban on disparaging trademarks unconstitutional as it was contrary to the 1st Amendment right to freedom of speech. The case related to a rock band seeking trademark protection for their name – THE SLANTS. This was considered racially disparaging towards people of Asian descent, and the USPTO therefore refused to register the mark. The SCOTUS said, “speech may not be banned on the ground that it expresses ideas that offend”. Six months later, the 2nd Circuit held that the Lanham Act’s ban on registering immoral or scandalous marks also violated the 1st Amendment (In re: Erik Brunetti, Dec. 15, 2017). Therefore, a clothing company could register the mark “FUCT”.

One may or may not agree with these conclusions, and certainly an argument can be made that the EU constitutional setting lacks the Bill of rights which instead endows the US Constitution. Nonetheless, also considering the ghosts of past dictatorships whose first instruments were, not surprisingly, the curtailing of freedom of speech, we wonder if after all, even bad taste deserves protection….

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.

“as EUIPO noted […], it is undisputed that in the field of art, culture and literature, there is a constant concern to preserve freedom of expression which does not exist in the field of trademarks.” – I assume that this consideration is only in respect of the grant / refusal of registration.

I have two objections:

The first is that the judgments of the GC are only appealable to the CJEU, but not to the ECtHR as the EU has not acceded to the ECHR.

The second is that the EU has a Bill of rights, that is the

Charter of Fundamental Rights, whose Article 11 guarantees the freedom of expression, which corresponds to Article 10 of the ECHR. Article 6(1) TEU recognises the Charter as having the same legal value as the Treaties ( C‑229/11 and C‑230/11, paragraph 22).

Article 52(3) of the Charter states that ‘in so far as [the] Charter contains rights which correspond to rights guaranteed by the [ECHR], the meaning and scope of those rights shall be the same as those laid down by [the ECHR]. This provision shall not prevent [EU] law providing more extensive protection’. The minimum threshold of protection of the rights guaranteed is thus to be determined not only by reference to the text of the ECHR, but also, inter alia, by reference to the case-law of the Strasbourg Court ( Case C‑704/17, opinion AG).