This case, L’Oréal Société Anonyme & L’Oréal (UK) Limited v RN Ventures Limited [2018] EWHC 173, involved a claim for infringement of both European Patent (UK) 1 722 699 B1 (“the Patent”) and Registered Community Design Nos. 000407747-001 (“the 747 Design”) and 001175046-001 (“the 046 Design”) (collectively “the RCDs”). The validity of the patent and the RCDs was not challenged by RNV.

Whilst the majority of the decision relates to the legal issues surrounding the claim for patent infringement, this blog post will focus on the claim for infringement of the RCDs.

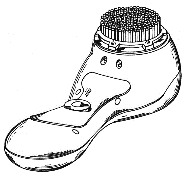

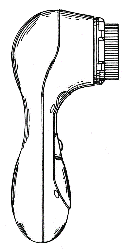

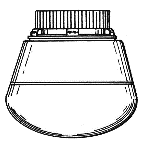

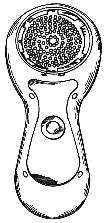

The product at issue is a handheld device which is used in the treatment of acne by deep cleaning facial pores. The device uses an oscillating circular head with rings of bristles arranged in concentric circles which, when used on the face, help to remove skin blockages that can cause acne.

RNV manufactured a similar product under its Magnitone range, and the claim is against certain products within that range.

Both sides relied on the evidence of expert witnesses in relation to both the claim of patent infringement and the claim of design infringement.

It was accepted by L’Oréal early on in the trial that the 747 Design formed part of the design corpus of the 046 Design. Consequently, the scope of the 046 Design was very narrow and it was found that none of the Magnitone products complained of infringed the 046 Design.

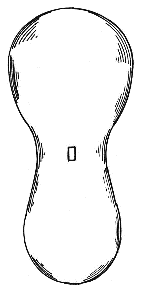

Representations of the 747 Design are as follows:-

The Magnitone ‘Barefaced’ device:-

The Informed User

Referring to the summary of the law as set out in Samsung Electronics (UK) Ltd v Apple Inc [2012] EWHC, Carr J defined the informed user in this case as the observant user of powered skin brushes.

The Existing Design Corpus

Article 7 CDR 6/2002 excludes designs which ‘could not reasonably have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned’ i.e. are too obscure to be known by the informed user.

L’Oréal tried to challenge the prior art relied on by RNV on the basis that, whilst not being excluded by Art. 7 CDR, it nonetheless fell outside the design corpus because it would not impact on the informed user’s awareness of the normal design features and RNV had not produced any evidence that the informed user would be aware of the prior art i.e. evidence of substantial marketing of the prior art etc.

Case law on this point was carefully considered and, drawing on the CJEU judgment in Cases C-361/15P and C-405/15 Easy Sanitary, L’Oréal’s argument was rejected. It was found that if L’Oréal’s position were followed, it would introduce an additional hurdle of needing to prove that the informed user was aware of the prior art in order for it to be considered as part of the design corpus.

Carr J concluded that such a requirement could lead to a situation where factors such as the volume of marketing, advertising expenditure etc. would play a role in the assessment of whether or not the informed user was aware of the prior design. This could lead to a situation where prior art which should form part of the design corpus would be excluded if there had been insufficient promotional activity around it.

The conclusion is that if prior art is not excluded by the exception in Art. 7 CDR, it is capable of forming part of the design corpus. There is no additional requirement to show that the informed user must be ‘aware’ of a prior design, where that design is not so obscure that it is excluded from the design corpus, but has not been widely marketed within the sector.

Effect of the Design Corpus and Design Freedom

If the differences between the registered design and the pre-existing design corpus are small, then small differences may avoid infringement. However, the greater the design freedom, the wider the scope of the monopoly and vice versa.

RNV tried to argue that the design freedom was very limited due to the functional requirements and technical aspects of the product at issue.

The expert for RNV, Mr Herbert, submitted that there were limitations on the design freedom because: (i) the design must incorporate a brush head of 3 – 5 cm diameter in size; (ii) the brush head could only be positioned on the axis in a limited number of ways; (iii) the handle had to be sculpted to create ergonomic grip; the design needed to incorporate batteries etc.; (iv) the brush head needed to be removable; (v) the product needed to be controlled whilst in use; (vi) the product must pass consumer testing; and (vii) the product must be economical so had to be made from commonly available plastics.

Whilst some of Mr. Herbert’s arguments were accepted, overall, it was found that, even within these parameters, the designer had a wide degree of freedom in relation to the design of the Magnitone product.

Comparison of the 747 Design and the Magnitone Products

RNV divided the 747 Design up into its distinctive and non-distinctive elements and then went on to compare only the distinctive features with the Magnitone products. It argued that the overall impression was different because there were insufficient similarities between the distinctive features of the 747 Design and the Magnitone product.

This argument was rejected on the basis that the test is whether or not the overall impression (which includes the combination of distinctive and non-distinctive features) is sufficiently similar to the registered design. By artificially dissecting the 747 Design and then only comparing the distinctive elements with the Magnitone product, RNV had not correctly compared the two.

The overall impression was found to be very similar.

The Decision

It was found that the Patent and the 747 Design were infringed by RNV.

The case serves as a neat reminder of the law on Registered Community Designs and the infringement assessment. The discussion around the design corpus and the level of knowledge attributed to the informed user is particularly interesting. The decision will be welcome news for brand owners seeking to rely on their RCDs to prevent competitors from creating and marketing look-alike products.

Keep an eye out for our upcoming blog on the impact of Brexit on EU Registered Designs following the EU Commission’s draft Brexit agreement.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.