The ”Pearl” decision by the Federal Supreme Court (BGH) may not be brand new (15 October 2020), but it is interesting in many respects. This post will deal with the similarity of goods.

Facts

The plaintiff owns an EUTM, registered in 2009, and a German registration, from 2003, for the word PEARL. Both are protected and used for ”bicycles”.

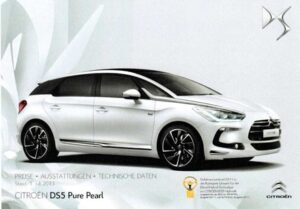

The defendant produces cars, bicycles and scooters. It owns the EUTM PURE PEARL, registered in 2013. The EUTM is protected for ”vehicles, apparatus for land transportation, motor vehicles, parts thereof.” The defendant’s parent company is Peugeot S.A., which owns the “Citroen” and ”Peugeot” marks. Between 2011 and 2013, the defendant sold two limited editions of cars named ”CITROËN DS 4 Pure Pearl” and ”CITROËN DS 5 Pure Pearl”. In advertising, the mark was used like this:

The plaintiff sued for the infringement of its ”PEARL” registrations. It prevailed in the first instance (Landgericht Hamburg, Regional Court of Hamburg) and lost in the second instance (Oberlandesgericht Hamburg, Court of Appeals of Hamburg). The Court of Appeals found that, while the signs were similar, bicycles and cars were not.

Decision

The Federal Supreme Court (BGH) considered the Court of Appeal’s reasoning to be deficient and referred the matter back to it.

Nevertheless, the BGH agreed with the legal principles the Court of Appeals applied:

- In order to assess the similarity of products, all the relevant features of the relationship between the products should be taken into account. Those factors include their nature, their intended purpose, method of use and whether they are in competition with each other or are complementary (see e.g. ECJ Sunrider, para. 85).

- It is equally relevant whether products of the respective kind are usually produced by the same companies or produced under the same companies’ control or whether the products share the same distribution channels.

- Further, pursuant to a principle applied by the BGH on a regular basis, goods (or services) are only dissimilar if, under the hypothesis of identical signs and a high distinctiveness of the older mark, there still would be no risk of confusion because of the differences between the products.

The BGH also agreed with the Court of Appeals’ findings that cars and bicycles generally had the same purpose (transportation), but that they differed in nature (e.g.: motor on the one hand, pedals on the other), in the legal framework surrounding their use and in their distribution channels.

Climate Change Makes Cars and Bikes more Interchangeable

What the BGH did not agree with was the Court of Appeals’ conclusion that the public did not assume that bicycles and cars are produced by the same companies or under the same companies’ control. The Court of Appeals had disregarded the undisputed fact that Peugeot S.A. also produced bikes and had done so for a long time. Consequently, the Court of Appeals had not dealt with the follow-up question of whether the manufacturing of bikes by Peugeot S.A. was just an anomaly, with no impact on the public’s perception. The Court of Appeals had equally disregarded the plaintiff’s undisputed factual arguments in connection with the climate crisis. The argument went that the climate crisis (as well as traffic congestion in the cities) had sparked a trend among consumers, city planners and officials to substitute cars with bicycles. Producers thus prepared for a switch to the production of bicycles instead of cars in the future. Under these circumstances, members of the public considered bicycles to be an alternative to cars.

Licensing Practice as a Factor for Similarity

The BGH agreed with the Court of Appeals on whether the public may assume a licensing connection between car and bike manufacturers and on the circumstances under which such an assumption might be relevant for the question of similarity. These considerations are worth taking a look at, too:

- The mere fact that trademark owners grant licenses to their marks for goods other than the ones the mark is protected for does not mean that the goods are similar (note: These are not actually licenses in a narrow sense but constitute a mere acquiescence on the part of the trademark owner). Typically, such licenses merely transfer the positive image of the licensed mark to the licensee’s goods – goods, which may be entirely dissimilar in nature to the protected goods. Therefore, to cite a prominent case, just because car producers grant licenses to the producers of toy cars, cars and toy cars are not similar (see BGH – Opel Blitz II following ECJ Autec). Such cases of dissimilar goods are dealt with under the regime of well-known marks.

- If, however, the products in question are, to a certain degree, similar in function, the public may assume a license by which technical know-how is transferred to the licensee. A license assumption of that kind may be a factor in determining similarity.

- There is no apparent reason for the public to assume a technology transfer from bike producer to car producer. Even if the public assumed a reverse transfer, from car producer to bike producer, that would not be relevant in the PEARL case, as this was about a false association with the plaintiff’s goods in the face of the defendant’s advertising, not the other way round.

Remarks:

- According to the “Similarity Tool”, EUIPO and most national trademark offices consider cars and bicycles to be clearly dissimilar. This position is worth reviewing, when one takes into account the market changes recognized by the BGH.

- The argument of a license assumption in connection with the similarity of goods has to be treated with caution: It tends to be circular in cases of a risk of confusion. A license is needed (only) if the respective use of the mark would create a risk of confusion, but a risk of confusion requires the similarity of goods.

- Further, the general public has rather vague and often false ideas about what kind of use requires a license from the trademark owner. For these reasons, the question of a license assumption should not be treated as a true relevant feature of the relationship between the goods, but rather as a test of whether the finding of similarity or dissimilarity seems sound.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.