We all know that highly famous marks enjoy a kind of “universal” protection for (almost) any goods and services. However, for only “average” well-known marks”, the threshold of necessary closeness depends on how well-known the trademark is, on the similarity of the marks, and on the type of injury.

Background of the case

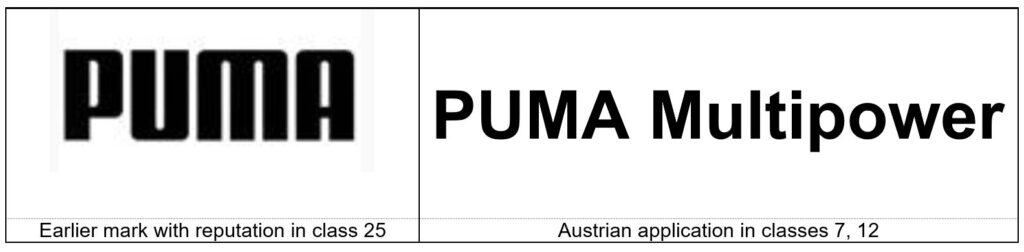

In a recent opposition case, the Higher Regional Court Vienna (“HRC), had the rare opportunity to shed some light on the scope of protection of the well-known trademark “PUMA” as against a similar mark applied for entirely dissimilar goods (decision of 22.03.2023, case 33 R 80/22k). Puma’s earlier EUTM (depicted above) covers (inter alia), and use was proven for, sports shoes, sportswear and accessories in class 25. The Austrian application for “PUMA Multipower” by the German company Agrowelt GmbH claimed protection for a wide array of goods in classes 7 and 12 (machines, machine tools, excavators, bulldozers, land vehicles, including lifting devices and telescopic handlers, see: https://puma-multipower.de/). Puma claimed both a likelihood of confusion and raised reputation claims.

The Austrian Patent Office had dismissed the opposition. In spite of acknowledging the similarity of the marks and the reputation of PUMA, it held the goods to be dissimilar overall and to serve completely different purposes. The relevant public would not overlap, thus, no exploitation of reputation.

The reasoning of the Higher Regional Court (HRC)

The HRC upheld the opposition on the basis of reputation. It considers the earlier mark to be very well known in the European Union: PUMA had proven extensive use and a degree of public recognition of 82% in Germany, a high market share and advertising expenditure in Austria and in the EU).

According to the HRC, such a particularly high awareness of a brand can go beyond the public actually targeted by the mark, and the more clearly and “undistortedly” the earlier trademark is adopted as part of the younger sign [i.e. the more similar the younger sign is], the more likely it is that the public, faced with that younger mark, would perceive it as a reference to the famous trademark of the opponent and its company name, even for goods and/or services, for which the earlier mark is not well-known, and would thus associate the marks in conflict.

The HRC also finds an overlap of the relevant public: The earlier mark’s sporting goods are aimed at end consumers, and the public addressed by the class 7 and 12 goods of the younger mark will be, at the same time, also consumers of sporting goods. Since the awareness of the PUMA mark among consumers is that high, they will be aware of the earlier PUMA mark also when being confronted with PUMA Multipower machines. Since the marks were highly similar, the public would establish a link between them also in relation to non-similar goods.

Of the grounds under Art 9 (2) EUTMR, Puma had invoked that the use of the younger mark would take unfair advantage of the reputation and the distinctive character of the earlier EUTM.

The HRC focused on the latter: Taking unfair advantage of distinctiveness encompasses impairment of the distinctive character and the advertising power of the trademark. The infringer uses a well-known trademark to attract the attention of the public to himself and his product and thus achieves a communication advantage, without having to make any efforts of his own.

It is settled case law in Austria (4 Ob 19/21d – Absolut, 17 Ob 15/09v – Styriagra), that when using an identical or similar sign, unfair motives may be assumed because of the obvious possibility of exploiting the attention to well-known trademarks. Thus, exploiting the distinctiveness of a famous mark indicates unlawfulness, unless the infringer is able to prove specific justifying circumstances. The HRC found the registrant’s allegation that the “Puma” element in its mark referred to ancient INKA mythology not convincing. Nor could the registrant rely on a long standing proprietary use of its mark, independently from Puma. Consequently, the opposition was upheld based already on that ground, taking advantage of the reputation was not examined.

Discussion

What is missing in the equation is a statement as to why or how the younger mark was used to exploit (e.g., in the Absolut case, the Supreme Court referred to the use of a highly similar design, and in the Styriagra case, the parody-like alusion, albeit in an exploitative way), and on how this factors into the overall assessment of the case (requirement, which the EU Case law emphasizes regularly, e.g. C‑252/07 – Intel, paras 41, 42, or C‑552/09 – TiMiKinderjoghurt, para 56). On balance, however, the result appears correct.

As a consequence, trademark applicants in Austria should beware adopting famous marks with a wide scope of public recognition among consumers in the EU, even for dissimilar goods which are addressed to a professional public.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.