A recent Court of Appeal decision revolved around the fast-food chain, Morley’s, and use of a similar trade mark by a lesser-known chain called Metro’s (including seven franchisees). Given the reputation of Morley’s in the fast-food industry, it had pre-established good will amongst consumers (having operated since 1985). Conversely, Metro’s has operated since 2015. The main issues regarding trade mark use in this matter were the confusingly similar nature of the marks and an agreement signed in 2018. While considering these points, this article will discuss this judgment by exploring these factors: likelihood of confusion between the marks; the grounds of appeal and how the Court of Appeal arrived at its decision.

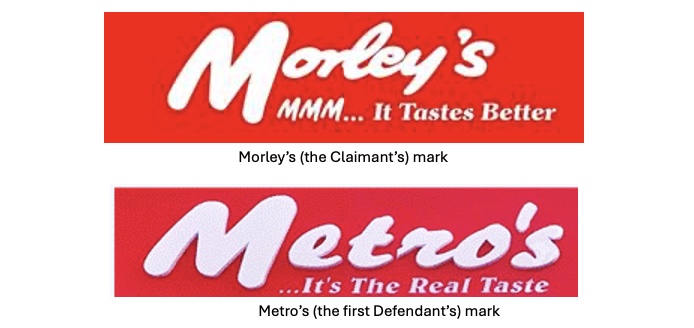

For illustrative purposes, the respective marks are displayed below:

Upon even a superficial inspection, one can conclude that these marks are confusingly similar. It is worth detailing how the judge in first instance arrived at this conclusion. They went through the usual factors that determine if there was a likelihood of confusion, namely: the marks must appear confusingly similar to the average consumer; the average consumer will perceive the mark as a whole, irrespective of nuances; marks should be considered with regards to their overall impression while taking into account any dominant elements; the similarity of goods and services covered by the marks; if the earlier mark has a highly distinctive character; mere association between the marks is insufficient; prior reputation of a mark alone does not give rise to a likelihood of confusion; and if association between the marks leads a consumer to believe the businesses are economically linked. In assessing these factors, the judge ruled that there was a likelihood of confusion.

The Defendants appealed this judgment on these grounds: the definition of average consumer (most, not only the defendants felt the judgment was incorrect in this respect); the degree to which the marks appear highly similar (most felt that the names of each store were different enough to eliminate any confusion); the conceptual comparison of the marks; the context of use of the marks; the effect of the 2018 agreement; the effect of this agreement on the franchisee Defendants; breach of this agreement by the Claimant; and the similarity of other marks used by the Defendants (namely the MMM trade mark) to the Claimant’s mark pictured above.

The Defendant submitted that the judge erred in determining the relevant class of consumer as they categorised them as low-income households and people out late at night, usually intoxicated, and looking for a quick, cheap meal. Lord Justice Arnold maintained that, even if this categorisation were inaccurate, it had no impact on the finding of the marks to be confusingly similar. The argument on degree of similarity was easily dismissed due to factors such as the colours, fonts, tagline, etc. Any argument against the contextual comparison was easily dismissed because the wording of each tagline of the marks rendered the subject matter similar. Context of use was also dismissed as these marks were both found on restaurant facias, menus, etc. With regards to the 2018 Agreement, at the time of the agreement, the Defendant agreed to use this mark:

Given the differences between this and Metro’s mark seen further above, Lord Justice Arnold found the agreement did not encompass the Defendant’s mark in its current form. As for the impact of this agreement on the franchisee Defendants, he ruled that this agreement did not apply to them as they were not expressly named in the agreement. Any claims of breach of this agreement by the Claimant were dismissed on the same grounds that were used to dismiss the arguments that the Defendant(s) had not breached this agreement. Finally, the Defendants used further marks including the “mmm” element from the Morley’s mark. It was maintained that this mark was still confusingly similar.

The main takeaway from this is brand owners can see that a mere lookalike can lead to confusion irrespective of the brand names. While this has not changed the position for establishing likelihood of confusion, it has provided a textbook example of what constitutes likelihood of confusion.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.