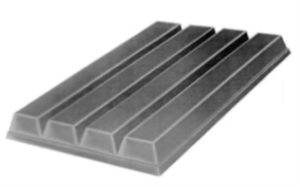

Nestlé was last month dealt another blow in its relentless bid to register the 3D shape of its famous four-fingered bar. The Court of Appeal (CoA) of England & Wales last month upheld the High Court’s earlier decision, rejecting the four bar Kit Kat.

The background to the case can be found here, but the crux of the issue is that Nestlé and Cadbury were battling it out over whether the shape of the KitKat bar is distinctive enough to be protected as a trade mark. Nestlé said it was, having launched in the 1930s and acquired distinctive character since such time; Cadbury argued that the shape was not distinctive enough to be protected as a trade mark and that to do so would grant an undeserved monopoly.

The discussion again focused around a very technical point relating to the correct approach in assessing acquired distinctiveness. Nestlé submitted that it would be sufficient to show that consumers perceive the mark as originating from them, as opposed to having placed any reliance on the mark when making a purchase. As such, the Hearing Officer, in applying a reliance test, had adopted the wrong approach.

The issue of perception vs reliance underpins the Kit Kat saga and is one that has been discussed at length on appeal. It was held in Nestlé v Mars that acquired distinctiveness can result from both use as part of or in conjunction with a registered trade mark provided that consumers perceive the goods or services, designated exclusively by the mark applied for, as originating from a given undertaking.

The CoA rejected Nestlé’s perception argument and found that Nestlé had not shown reliance. The problem for Nestlé was that it could not show use of an unbranded four-finger bar to indicate that it was a KIT KAT. The three justices of the CoA agreed that for marks like the four-fingers i.e. those used in conjunction with a registered trade mark and where the mark is not visible at the point of sale, showing consumer reliance can be difficult.

The justices were quick to highlight that it is not a necessary precondition of acquired distinctiveness to show that consumers have relied on the mark as an indicator of origin, rather the mark, used on its own, needs to have acquired the ability to demonstrate exclusive origin. Whilst it is unfortunate that the CoA held that it would “unwise” to elaborate on how this might be achieved, the judgment does provide some useful reminders on what will assist brand owners, including what not to do.

The CoA built upon the Hearing Officer’s criticisms of the use of the evidence provided by Nestlé, namely:

- there was no evidence that the shape of the product has featured in Nestlé’s promotions for the goods for many years;

- the product is sold in an opaque wrapper and until recently before filing, the wrapper did not show the shape of the goods;

- there is no evidence that consumers use the shape of the goods post purchase in order to check that they have chosen the product from their intended trade source;

- the fingers of the product had always been embossed with the Kit Kat logo;

- there were other finger-shaped chocolate products on the market prior to the application date.

Another thing that is clear from the judgment is the need for applicants to show that they have educated the public that the mark is distinctive to them. This is not a new concept by any means, but what is clear is that there is a level of responsibility on the part of the brand owners themselves to do this – legal argument alone can only go so far.

This commentator’s last blog post on this case remarked that the subtext on the High Court decision was that Nestlé were being penalised for the fact that they rarely used their sign in a way that suggests that they think of it as a trade mark which is intended to indicate origin. Here, the CoA have been, helpfully, more explicit in this regard, quoting Jacob J (as he was then) in Nestlé v Unilever:

There is a bit of sleight of hand going on here…. The trick works like this. The manufacturer sells and advertises his product widely and under a well-known trade mark. After some while the product appearance becomes well-known. He then says the appearance alone will serve as a trade mark, even though he himself never relied on the appearance alone to designate origin and would not dare to do so. He then gets registration of the shape alone. Now he is in a position to stop other parties, using their own word trade marks, from selling the product, even though no-one is deceived or misled.

Based on the above, it is clear that trade mark reliance should start at boardroom level or the factory gates. Brand owners would do well to show ‘aspirational reliance’ of their product’s shape during launch, thereby laying the foundations for showing acquired distinctiveness. This is something that is done, by coincidence or design, better in other countries, for example, the commonplace use of ‘look for’ pointers by brands in the U.S. to highlight their USPs. Doing so can only serve to validate the responses of interviewees in showing that they have placed reliance on the mark.

There is a final question here: would Nestlé would have been better served by simply accepting the Hearing Officer’s decision, which allowed the mark through on inherent grounds for “cakes and pastries”? Whilst Cadbury would have no doubt have appealed this decision, it is questionable whether that issue considered alone would have been decided differently. A significant advertising and marketing push by Nestlé to take on board the Hearing Officer’s comments (e.g. a Kit Kat sold in vacuum packs to show its shape, product displays emphasising the shape, and campaigns around four fingers) followed by a refiling after a few years of such use may have been a prudent option. Indeed, as noted by the CoA, the appeals in this case have focused more heavily on the issue of perception vs reliance than at the UK IPO level. A refiling would have allowed this issue to be properly explored, rather than the limited argument available on appeal.

For now, hindsight is 20-20, and Kit Kats are not four finger trade marks in the UK.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.