As reported earlier by this blog, there is a discussion in Germany whether an infringer who has received an injunction has to actively recall the products. And the German recall-saga continues, as the Higher Regional Court (OLG) of Düsseldorf has just recently decided in an unfair competition matter that the obligation to cease and desist from distributing products does basically not require the defendant to recall products from its independent commercial customers, nor to request the resellers to suspend the sale of the products (decision of 14 February 2019 in Case I-20 W 26/18). This approach is in plain contrast to previous decisions of the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH). The CJEU should now set the legal framework as soon as possible, in light of the potential European dimension of the issue.

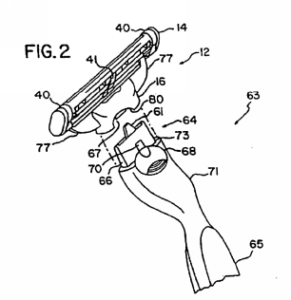

The OLG’s reasoning is in line with another decision of the OLG concerning a patent dispute about razor blade units (see below pictures), which had come to the same conclusion (decision of 30 April 2018 in Case I-15 W 9/18, lifting a decision of the Regional Court/LG Düsseldorf of 18 July 2017 in Case 4a O 66/17).

The OLG’s view does not correspond to the approach of the BGH, which is notable because the BGH is competent to revise the decision of the OLG. According to the First Civil Senate of the BGH (competent for matters concerning trade marks, copyright and unfair competition, amongst others, but not for patents) the defendant shall, as a basic rule, recall the infringing products from its commercial customers. In interim injunction proceedings the defendant may “only” be required to ask its resellers not to sell the subject products for the time being (which in fact is equal to a recall, in particular in relation to fashion products or foodstuffs, which are only marketable and sellable for a limited period of time). The concrete measures to be taken depend on each individual case (see decision of 11 October 2017 in Case I ZP 96/16). The BGH has faced significant opposition by other courts and legal professionals for interpreting cease and desist orders in such an extensive way. There are strong arguments that the approach of the BGH goes too far. A product recall can harm the business relation between the supplier and its commercial customer for the future, even if the supplier was not aware of any unlawful behavior. One of the key issues is that the defendant does not know in advance which active measures to take, because the cease and desist order is silent in this respect. These uncertainties do not seem reasonable, because under German IP law there are independent, specific provisions tailored to product recalls yet, requiring the plaintiff to explicitly apply for a recall.

At least there may be light at the end of the tunnel. First, the defendant in another matter filed a constitutional complaint against the contested practice of the BGH (Case 1 BvR 396/18, pending), pointing out that the German approach shall be revised by the CJEU (in that case for European Union trade marks). These allegations are correct, because according to the laws of many other EU member states a simple cease and desist-claim does not imply a product recall. Different approaches within the EU can cause significant discrepancies and uncertainties in cross-border litigation cases and harm the free circulation of goods. Second, even on a national level the different Civil Senates of the BGH do not seem to take a uniform view. In particular the Patent Senate appears to take a more restrictive approach than the First Civil Senate, so finally the higher Common Civil Senate of the BGH may set a uniform framework for Germany, unless the CJEU clears the matter in advance.

Still, in respect of IP-matters related to Germany the defendant should comply with the extensive obligations imposed by the BGH, until there is a clarification. The defendant is advised to try to clear the scope of a cease and desist order in due time, in particular whether the plaintiff expects him to execute a product recall or not. Such clarification might also be in the plaintiff’s interest, because he can be obliged to pay damages to the defendant if a court lifts an interim injunction later, or when a warning letter was unjustified.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Trademark Blog, please subscribe here.